Word Painting in Sonnet XVIII (Part II)

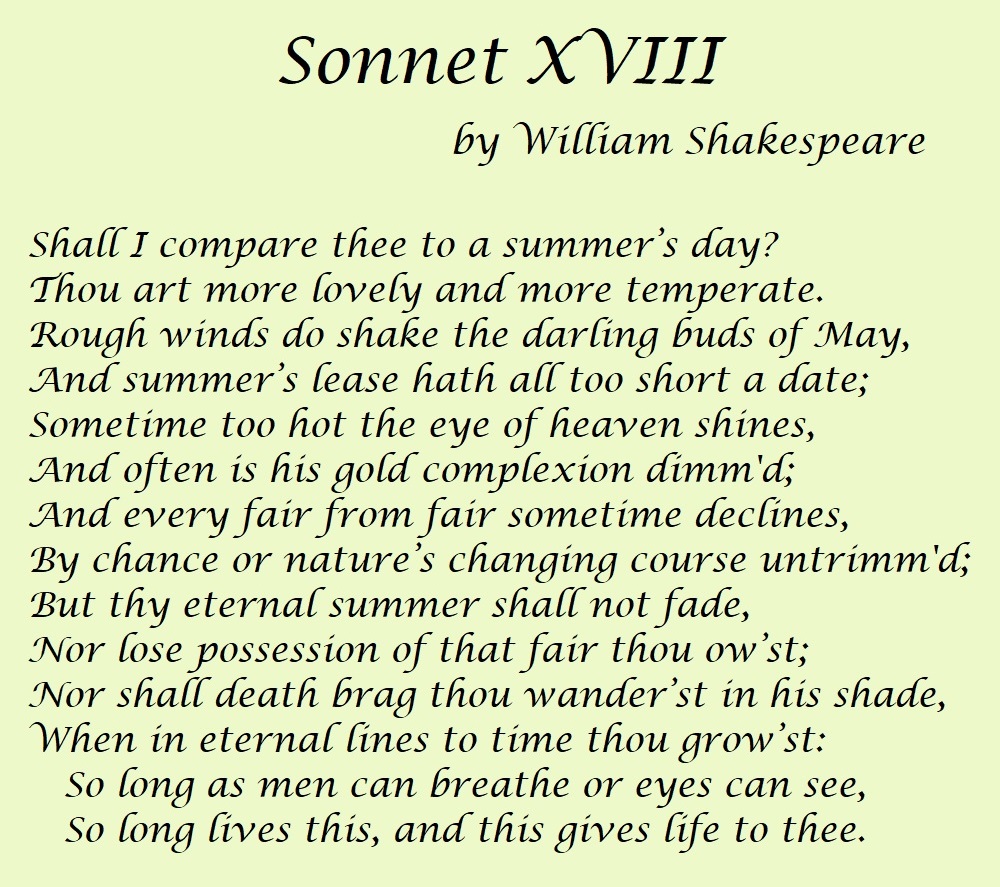

Part I of this series discussed word painting in my musical setting of Shakespeare’s Sonnet XVIII — that is, how the meanings of specific words and phrases are represented in the music. The focus in Part I was on word painting in the first eleven lines of the sonnet, but the central meaning of the poem appears in the last three lines.

This sonnet’s central idea is that the beauty of its human subject (believed by most scholars to have been a young man) is immortalized by the poem itself. The idea of immortalization becomes explicit in the twelfth line: “When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.” Here the “eternal lines” are the fourteen lines of the poem, a poetic self-reference. Through the magic of the poet’s art, the youth’s beauty is transformed from the ephemeral to the eternal, becoming preserved across all time. These words give rise to the most remarkable passage in the composition, which accomplishes a kind of temporal transformation in music.

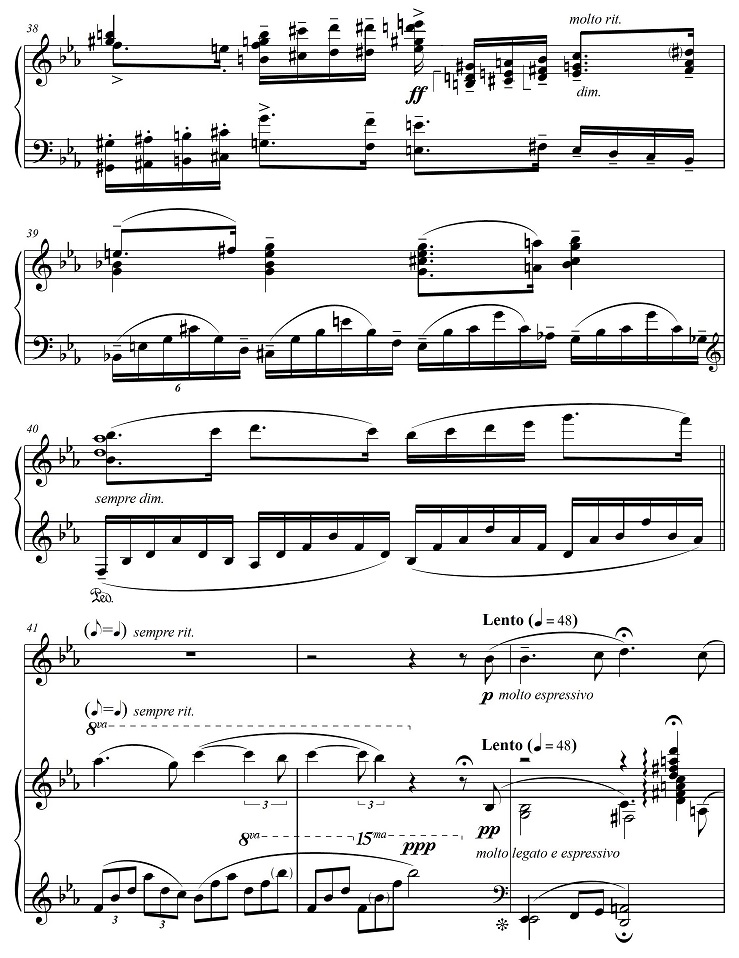

First, as might be expected, the word “grow’st” (measures 36-37) is accompanied by a dramatic crescendo, which ushers in the longest instrumental interlude in the work. The piano part then continues to build in excitement, realized through an accelerando while the crescendo continues. The melodic motive here derives from the opening of the piece, where it appeared in bar 6 of the vocal part with the words “to a summer’s day” (shown at right), but now presented within the piano’s cadenza in diminution with contrapuntal imitation between the two hands.

After the passage rises to a fortissimo climax in the middle of bar 38, the process reverses.

The music now diminishes in both speed and intensity. At bar 41, the note values change in such a way that hextuplets become triplets, but at a tempo comparable to that which preceded the whole passage. After a long fermata in bar 42, the recorder, which has been silent since bar 4, enters quietly and mysteriously, intoning a melody that seems to call out from Shakespeare’s own time. That melody is the work’s main theme, but presented at a slow tempo with expressive embellishments. The piano provides counterpoint to the recorder line, in a texture that becomes increasingly complex, reminding us of the rich polyphonic style of the late Renaissance.

Accompanying the temporal transformation and dynamic changes, this whole passage goes through a harmonic transformation, moving from the tonic E-flat major harmony at the beginning of m. 34 through rapidly changing chromatic harmonies to an E7 harmony at the climactic midpoint of bar 38. Then, as the music recedes from the climax, it moves toward a dominant-seventh (Bb7) harmony at bar 40, which is prolonged through m. 42. Note that the roots of E7 and Bb7 are separated by a tritone. In general effect, at least, we have traversed the circle of fifths.

In this score video, the work is realized by the beautiful baritone voice of Nathan Benjamin Guc, along with Tristän Clarence Rush on the alto recorder and myself on the piano.