Word Painting in Sonnet XVIII (Part I)

Shakespeare’s Sonnet XVIII (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) is one of the most famous poems in the English language.

In 1982 I composed a setting of this sonnet for baritone, piano, and alto recorder. After revising the work during the winter of 2018-2019, I recorded it on July 15, 2019 with baritone Nathan Benjamin Guc and with Tristän Clarence Rush on the recorder.

Like most of my music, this work is very Romantic, but it also has an antique flavor, suggested not only by the use of the recorder but also by some exotic harmonic progressions and prominent parallel fifths. I wanted to evoke some of the musical style of Shakespeare’s own time, which spanned the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. The setting makes particular use of the technique of word painting, that is, the literal portrayal of the meaning of the text in music. Word painting was a prominent device in late sixteenth-century madrigals — a period corresponding to the early part of Shakespeare’s creative life. Some of the uses of word painting in this setting of the sonnet are illustrated here:

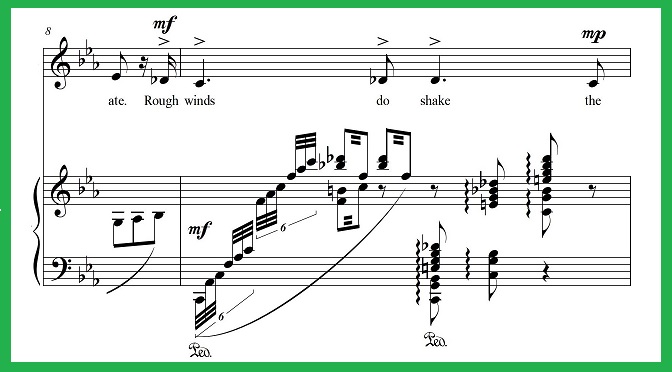

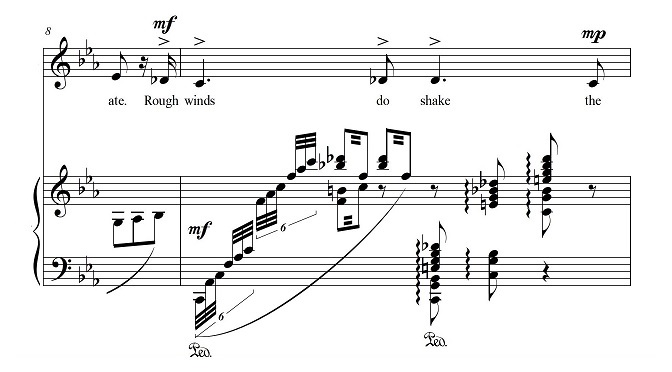

• In measures 8-9, Shakespeare’s words “Rough winds do shake” are accompanied by tumultuous rapid arpeggios, tremolos, and rapid rolled chords in the piano part.

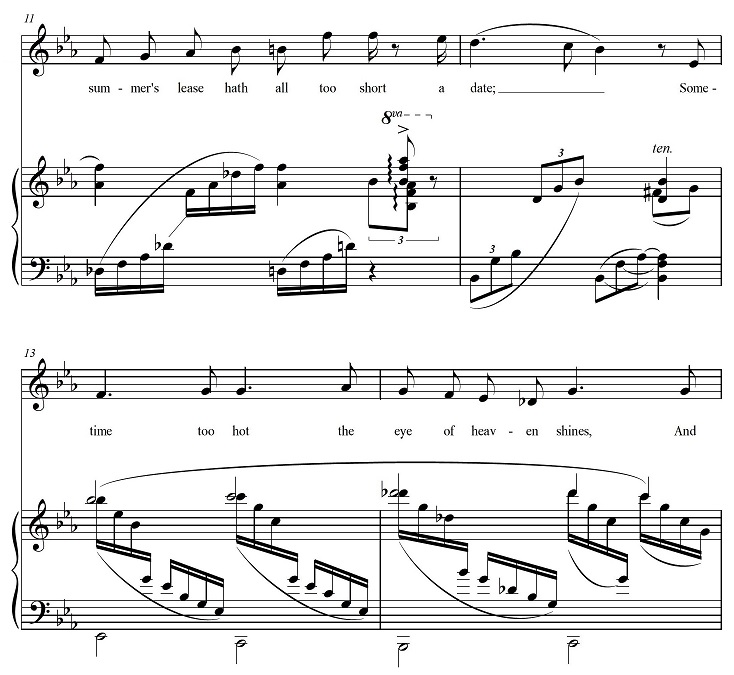

• In measures 11-12, Shakespeare laments that “summer’s lease hath all too short a date.” The word “short” here is realized by a sharply truncated note in the baritone part, followed by a brief rest. Then in the next two measures, the text says: “Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines.” The phrase “eye of heaven” references the sun, of course, and the piano part in mm. 13-14 features a high-register countermelody, with arpeggios descending from each melody note like waves of heat radiating down to the earth.

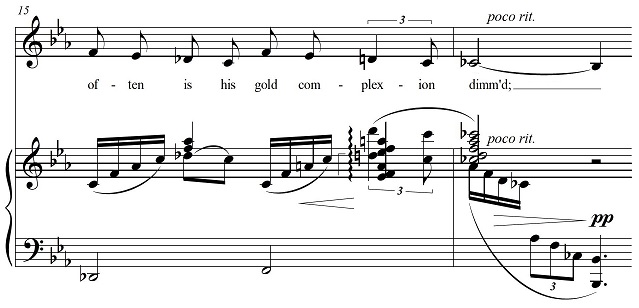

• Still speaking of the sun, Shakespeare writes: “Often is his gold complexion dimm’d.” In mm. 15-16, the word “gold” is accompanied by a bright F major harmony, and the subsequent dimming is represented by a descending chromatic line, where the C-flat is accompanied by a dark diminished-seventh harmony, along with a decrescendo and ritardando.

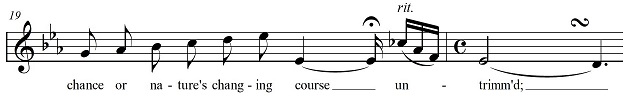

• Shakespeare alludes to the ephemerality of natural beauty in the words “nature’s changing course,” represented in mm. 19-20 by a meandering line in the baritone part.

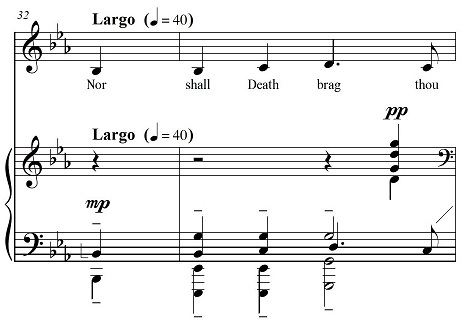

• Shakespeare’s reference to “Death” in the eleventh line of the sonnet is harmonized in the second half of m. 33 by an open-fifth chord (i. e., omitting the third, the “soul” of the triad), along with a deep and ghostly bass line.

The crux of the poem’s meaning, however, comes on the twelfth line of the poem, in the words “in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.” The “eternal lines” are the lines of the poem itself, which transform the transient beauty of the poem’s human subject into something everlasting. This mysterious transmogrification across time is represented in the music in a remarkable manner, to be discussed separately in Part II.