My Aesthetic Goals in the Piano Quartet

My Piano Quartet was composed in the fall of 1993, as part of my work toward an M.M. degree in composition at Georgia State University, which I completed in 1995. I revised this ambitious work extensively in 2018-2019, and a good recording was made in February 2020 by violinist Cari Sue Jackson, violist Camille Phillips, cellist Sarah Langford, and myself at the piano.

.

The document is a revealing snapshot of my musical outlook at that time. It begins with an explanation of the philosophical underpinnings of my music and of the aesthetic goals I was seeking to accomplish. A formal analysis of the Piano Quartet followed. In the near future I will be posting several posts to this blog about the quartet’s structure. Meanwhile, I have reproduced below (with some minor editing) the introductory section from the essay, explaining how my music grew out of my philosophical perspective. These words might also be thought of as a kind of manifesto, setting forth my viewpoint as a Romantic composer in the 1990s as contrasted with the anti-Romantic outlook that had prevailed through much of twentieth-century music.

| I will begin with a little philosophy, because my compositional style and method reflect my worldview — specifically, that reality has a specific identity, which human beings are capable of comprehending by means of a volitional process of mental integration, and that life is therefore not inherently dark and foreboding and meaningless, but potentially clear and joyful. This worldview has been largely rejected by twentieth-century intellectuals, a rejection apparent in twentieth-century music in particular, which more often projects a Wozzeck view of the world rather than one of rationality and light. My music is therefore directed toward the listener who revels in the use of his or her mind — the listener who enjoys the mental challenge offered by complex musical design but scorns obscurity, tedium, and chaos. My ideal listeners delight in the “aha” experience of a new integration, of recognizing that the fugal subject they hear is actually a variation on a previously heard theme, or that two melodic fragments heard a moment ago are now fit together in compelling counterpoint. They need not be trained in music theory, although to appreciate my music fully they need to focus and educate their ears, perhaps with the aid of repeated hearings. Even experienced performers may require a period of time to assimilate my complex harmonic vocabulary and intricate counterpoint.

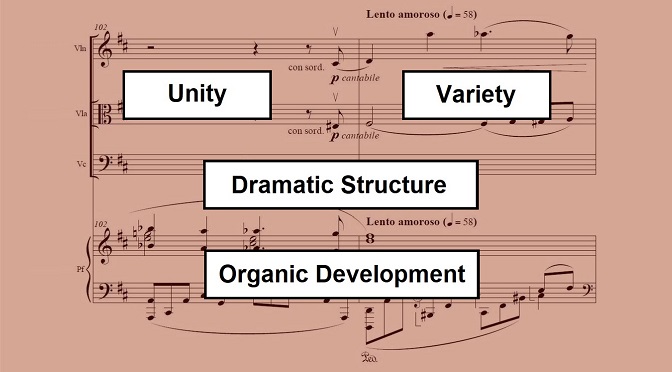

In order to provide this ideal integrational experience to the listener, I find I must observe certain essential principles in a composition: a sense of unity across the whole composition, so that it can unite a variety of thematic or stylistic elements into a coherent whole; a dramatic structure, in order that the work will make sense as it unfolds over time; and a sense of organic development, so that each passage will seem to arise naturally from what precedes it, such that even an intentional surprise will seem perfectly natural in retrospect. These principles determine not only the overall form of the work, but also the details of its style and texture. These principles are interpreted from the listener’s point of view, and not from the point of view of someone studying the score. A twelve-tone row, for example, could not impart unity to a composition if that row could not be identified by a listener — unless, perhaps, the row was calculated to have tonal implications, as in the Berg Violin Concerto. The human ear seems to me to be naturally adapted to grasping tonality, and hence my style is tonal. For the same reason, in imitative counterpoint I will choose a tonal imitation over a real imitation, if the tonal imitation can be recognized by the listener and makes more sense harmonically. I generally avoid devices such as extended retrograde imitation, since these cannot usually be perceived by the listener and therefore impose unnecessary limits to the compositional process. If my compositional style can be identified as Romantic, then that is because my style grows out of these concerns, and certainly not out of any wish to imitate any period of the musical past. |

If you are mystified by the reference in the first paragraph to “a Wozzeck view of the world,” I should explain that Wozzeck was the title character in an opera by Alban Berg. The opera is a good example of German expressionism, which I regard as very different from true Romanticism. I elaborated on that distinction in another part of the document: “The view of man implicit in Expressionism, perhaps best conveyed by the figure of Wozzeck, as the helpless, confused victim of an incomprehensible reality and of subconscious forces beyond his control, is antithetical to Romanticism.” I set forth my own view of Romanticism in this blog post from October 2016.