The Triptych Sonata

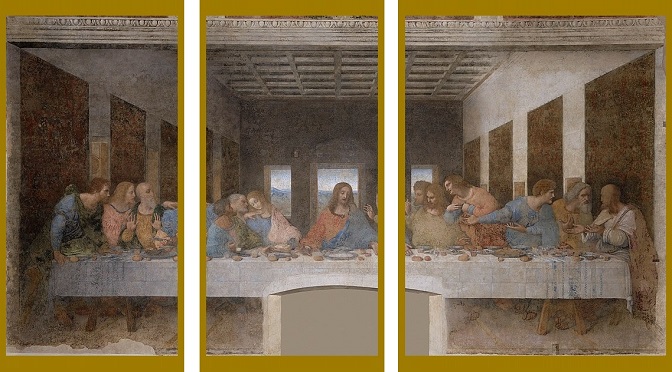

A triptych is a set of three panels presented side-by-side, each of which may or may not constitute a complete coherent picture on its own, but which combine together to create a complete picture. My Piano Sonata No. 3 can be thought of as a kind of musical triptych. Its three movements are designed to be played in sequence, producing a unified whole with its own tonal structure. The second (slow) movement can also be played independently, but neither the first movement nor the third movement would make good musical sense if played by itself.

The archetypical classical sonata consists of three or four movements, each of which can usually function as an independent piece of music. Occasionally, there may be thematic connections between the movements, particularly as the genre developed in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, each movement is like a picture that is complete in itself, executing a complete coherent tonal progression within a particular key. The first movement, for example, is typically in the familiar form known as “sonata-allegro form” (or sometimes simply “sonata form”), with an exposition setting up a tonic-dominant polarity, a development, and a recapitulation where all the themes are presented in the tonic, thus resolving the polarity.

If a musically perceptive listener were to approach my Piano Sonata No. 3 expecting these classical norms, the experience might be bewildering.

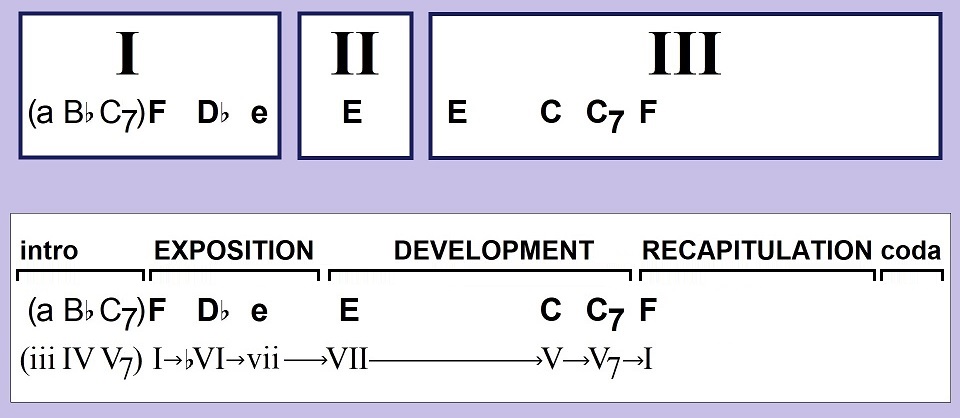

The first movement begins with a misterioso introduction that briefly visits several tonal centers before clearly establishing an F major tonality. A lyrical second theme is then presented in the rather remote key of D-flat major, which develops into an Agitato closing section in the equally remote key of E minor. The final bars, like the beginning, have a mysterious quality and a sense of inconclusiveness.

The second movement, in contrast, has a clear tonal structure. It begins and ends in E major. The opening uses motivic material from the first movement, leading into a serene, beautiful melody that starts at bar 15.

The final movement, which constitutes just under half of the entire work, begins with a quasi-improvisatory passage in E major and then passes through a variety of secondary tonal centers before arriving at C major and finally at F major.

The three movements provide the fast/slow/fast contrast one might expect in a three-movement classical sonata. But the middle movement is the only one that has a clear and complete tonal structure when played independently. Nevertheless, it is apparent that there is a large-scale tonal progression across the whole work. The three movements are analogous to the three framed panels in the triptych seen earlier. In combination they present a complete picture — a picture which we grasp by mentally removing the frames.

That picture includes the exposition, development, and recapitulation of classical sonata-allegro form, along with a coherent tonal progression within the key of F major. In thematic terms, the exposition comprises the first two movements, and the third movement develops and recapitulates the materials from the previous two movements.

Tonally, a polarity between the tonic F major and E major, which serves as a dominant substitute, is set up in the exposition. E major makes an effective substitute for the dominant since it is based on the leading tone in the overall F major tonality. It progresses to a true dominant (C and C7) by the end of the development, and the polarity is then resolved in the recapitulation and coda, which are centered on the tonic.

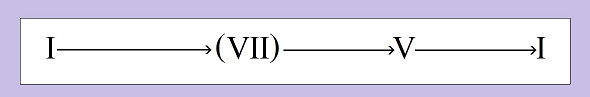

The overall tonal progression can be seen stripped down to its fundamental harmonies below.

Curiously, the same basic underlying progression can be found in my Romance for Oboe and Piano, where VII (based on the leading tone) also serves as a dominant substitute, progressing to V on its way back to I. The structure of the latter piece is discussed in this blog post, which also points to examples of the use of VII as a dominant substitute in two works of Rachmaninoff.