Vibrations of Sympathy

The violin was the first instrument I studied formally, and I took my first lessons around the time of my tenth birthday. As young children we hear music with a fresh ear, vividly aware of things that adults might not hear or might take for granted. One of the things I learned in my first few weeks as a beginning musician was that certain pitches, if I played them with exactly the right intonation, produced an exceptionally rich, beautiful sound. I eventually learned that what I was hearing was sympathetic vibrations from the instrument’s open strings and their overtones. Because of these natural sympathetic vibrations, certain keys sound better than others on the violin and other string instruments. I was reminded again of this fact when I mentioned not long ago that I was changing the key of a work I was transcribing to G major, in part because it is a more favorable key for strings, and a pianist friend of mine asked why that was so.

The open strings on the violin are tuned to G, D, A, and E. Perhaps the most favorable major key for the instrument is D major, where the roots and fifths of the tonic, subdominant, and dominant harmonies tend to resonate with the open strings, while the thirds of these chords resonate with their overtones. I do not think it is any coincidence that three of the finest violin concertos in the repertoire — those of Beethoven, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky — are all set in D major. The composers, after all, knew what they were doing. G minor, the key of the famous Bruch concerto, also works well on the instrument, with lots of resonances between the tonic and dominant triads and the two lower strings. The keys of A minor and E minor resonate very well with the two upper strings. Bach chose A minor for what is perhaps his most popular violin concerto, the wonderful Mendelssohn concerto is set in E minor, and Sibelius used D minor for his one violin concerto.

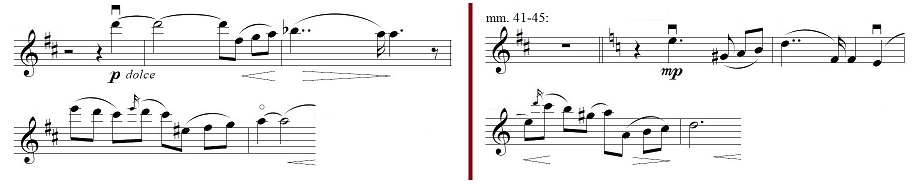

I chose D major for my Adagio for Violin and Piano. The B section, however, begins with a variant of the opening theme in A minor.

To my ear, the original theme (left) seems very peaceful, while the variant (right) is more intense and dramatic, partly because of the change of mode, and partly because of the way the intervals are modified.

Sympathetic vibrations also play an important role in the piano, especially because of the damper pedal, usually referred to simply as “the pedal.” “The pedal is the soul of the piano,” declared Anton Rubinstein (although the statement is sometimes attributed to various other pianists), and that role is realized in large part through sympathetic vibrations.

The term “damper pedal” is a bit of a misnomer, since the pedal lifts the dampers from all the strings of a piano, thereby “un-damping” them. We typically think of the pedal as a device for sustaining notes after they have been sounded. Thus the pedal can blend together the notes of an arpeggio, even if the arpeggio is too large to be sustained by the hand alone. More generally, a pedal can be used to connect tones that for technical reasons would be difficult or impossible to connect with the hands and fingers alone.

But the pedal also plays a more subtle role in changing the quality of a note, by enriching it with sympathetic resonances from those other strings with which it has shared overtones. There is a distinct difference in tone quality (or “timbre”) between a middle C played with pedal and the same note played without. An experienced pianist seeking to bring a rich sound to a beautiful melody will intuitively know to use the pedal, even in cases where it would be perfectly possible to play it legato without the pedal. (Of course, that same pianist will also know to change the pedal wherever necessary to avoid blending together sounds that should remain distinct.)

Students sometimes ask whether pedal should be used with Chopin’s famous Etude in E Major, op. 10/3. Since this étude is a study in achieving a fine legato with the hands and fingers, they ask, would using the pedal constitute “cheating”? My response to these students: “I play it with the pedal because the pedal gives warmth of sound, even if you are able to do all the legato connections without it. It is a beautiful piece of music, not just a technical exercise.”

This somewhat scratchy recording is from a 1986 recital, where I interpret the étude that included what Chopin considered his most beautiful melody.