The Elided Second Degree

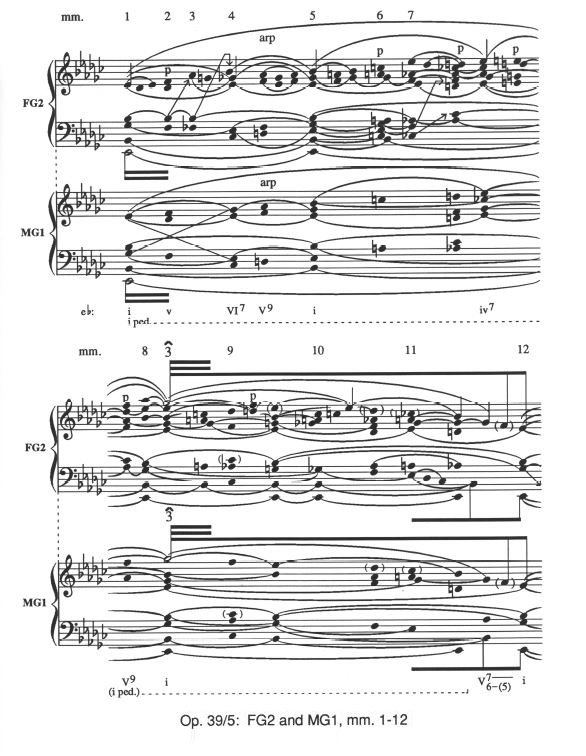

Many years ago I performed Rachmaninoff’s Etude-Tableau op. 39/5, and it remains one of my favorite works by the composer. To my ear it has a characteristic (and gorgeous!) Rachmaninoff sound. We can glean one reason from the Schenkerian graphs below, showing foreground and middleground for the first twelve measures of the piece. The graphs come from my 1999 dissertation.

Beneath all the surface ornamentation, the basic melodic motion in these measures is a descent from the third scale degree, represented by Gb5 in bar 9, to the tonic in bar 12. (The Gb5 is approached by an ornamented arpeggation that begins in the first bar.) The underlying harmonic motion is i-V7-i. Ordinarily, under those circumstances, we would expect the melodic Gb to pass through F (over the dominant) on its way to E-flat. Instead, Rachmaninoff hangs on to the G-flat over the dominant, omitting the expected resolution to the second scale degree, before passing directly to E-flat over the tonic. (The absent but implied second degree is shown in parentheses in the graphs.) The aural effect of this elision of scale degree 2 is experienced clearly at the end of bar 11. We hear a wonderful mélange of tonic and dominant harmony, with the bass and inner voices pointing toward dominant-seventh harmony while the melody wistfully clings to the third of the tonic triad.

As it turns out, this device, which I call the elided 2, is very idiomatic to the composer, occurring in work after work and explaining much of the characteristic Rachmaninoff sound. In each case, the elided 2 appears in authentic (that is, V-I) cadences where the third degree of the scale is held over the dominant harmony, resulting in a sonority that mixes tonic and dominant implications.

The elided 2 is not entirely unique to Rachmaninoff, however, and it is not too difficult to imagine how it probably evolved historically.

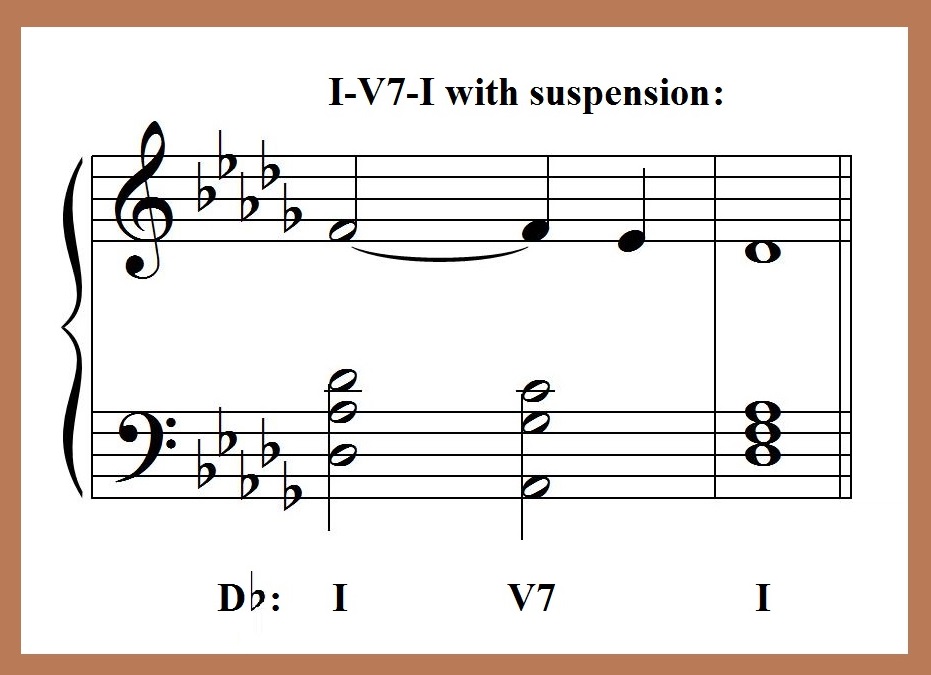

First, the commonplace progression from tonic to dominant and back can become tiresome, so composers often decorate it with a suspension.

In this D-flat major progression, the third degree of the scale is held momentarily over the V7 harmony, creating a passing dissonance that is resolved when it descends to the second degree on its way to the tonic. During that brief moment before the resolution, there is a slight suggestion of a mixed tonic/dominant harmony, but the suggestion is quickly dispelled by the resolution, and the suspended third degree is heard retrospectively as a nonharmonic tone.

But what if the suspension were held for a much longer period of time and emphasized by repetition, while its resolution is deemphasized? In the passage below from Un Sospiro, Liszt does exactly that, lingering lovingly on melody note F (scale degree 3) over the dominant-seventh sonority through an extended cadenza-like arpeggiation. A rest with a fermata follows, and a good pianist will probably preserve the mixed tonic/dominant harmony in the pedal through at least part of the rest. The same sonority is then repeated on the last beat of measure, with the resolution delayed until the very last sixteenth. Clearly, the composer intended us to savor this delicious dissonance.

The passage begins around 3:57 in my recorded performance of the work:

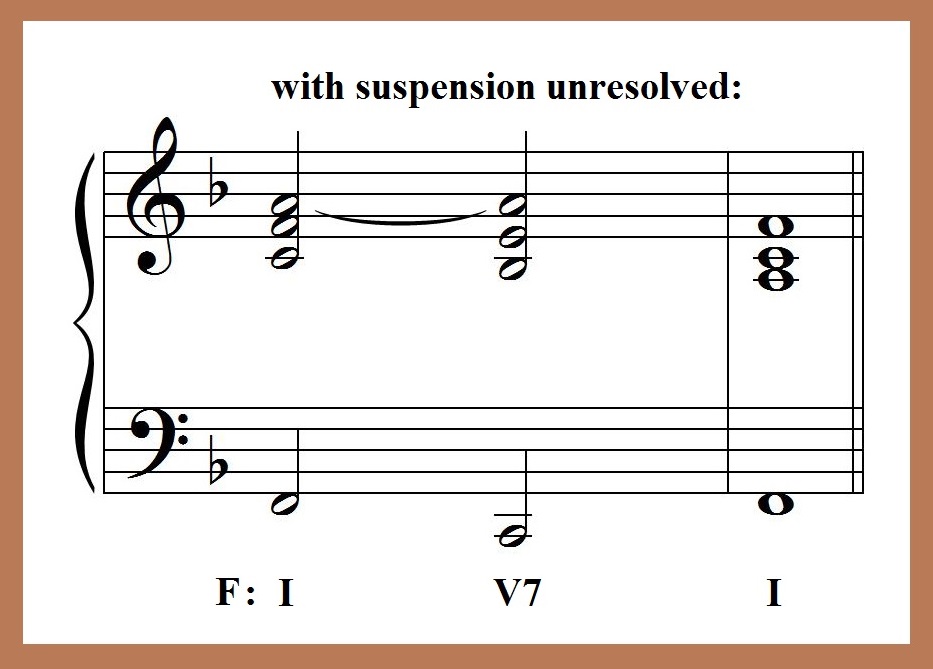

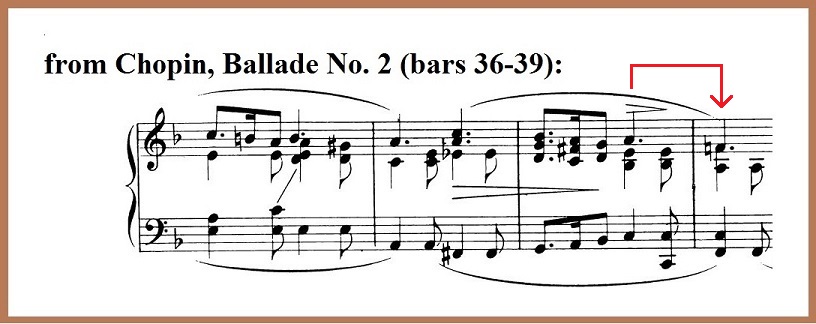

Chopin takes exactly that step in his Ballade No. 2. Instead of resolving to G (scale degree 2 in F major), the dissonant A resolves directly to F, resulting a true instance of the elided 2.

In fact, Chopin immediately repeats the unusual progression seven more times (not shown here) in succession, again clearly savoring the sonority. This Chopin example was pointed out to me by noted Schenkerian theorist Carl Schachter during a discussion of my dissertation (which was then underway) and my observations of the elided 2 in Rachmaninoff. It had escaped my notice even though I had performed this ballade myself. The passage begins around 1:58 in my recorded performance:

In contrast to the above examples, most of Rachmaninoff’s uses of the elided 2 are in minor keys, where it creates some special sonorities. I plan to discuss the relationship between the elided 2 and those sonorities in a later post to this blog.