SEVEN: Life at Meter’s Outer Limit

I related the “Seven Plus or Minus Two” principle to pitches and harmonic centers in an earlier post to this blog. But the mind of the listener must grasp meter as well as melody and harmony, and the principle also applies to meter. The maximum number of units we can grasp at once is about 7 +/- 2, unless we resort to “chunking” some of the units into a whole that we can understand as a single unit. That’s why we rarely see time signatures where the numerator is a prime number greater than 7. In fact, if your preferred fare is contemporary pop music, chances are you have trouble with prime numbers greater than 2. 😉

Of course, a meter such as 12/8 is not uncommon, but 12 is not a prime number, and we normally hear a piece in 12/8 time as having four chunks — that is, beats — of three eighth notes each. (That’s right, 12/8 meter has four beats to the measure, not twelve.)

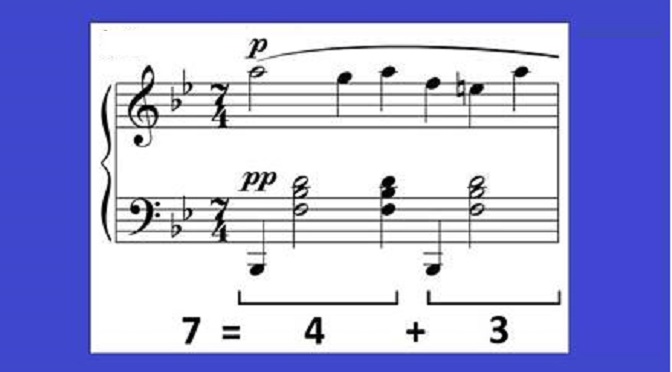

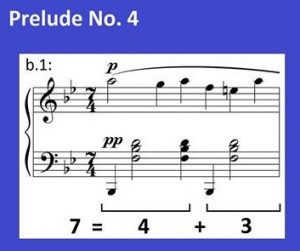

Perhaps because 7 is close to the limit of our cognitive capacity, even with 7/4 time we tend to subdivide each measure into chunks, which obviously cannot all be of equal length. In most of my Prelude No. 4, the bass pattern makes it easy to hear the 7 beats as subdivided into a chunk of 4 plus a chunk of 3.

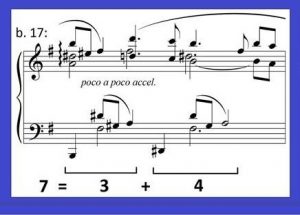

The passage starting at bar 17, however, suggests a (3 + 4) subdivision.

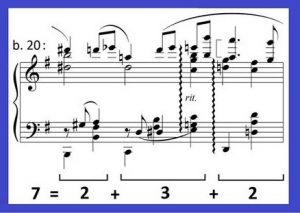

Bar 20 subdivides naturally into (2 + 3 + 2).

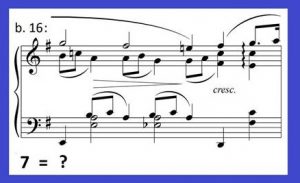

Bar 16 seems to me truly ambiguous; depending on whether you focus on the right hand or the left, it might be either (2 + 2 + 3) or

(3 + 2 + 2), among other possibilities. Listen to it in the score video and let us know how you hear it in the Comments!

These subtly shifting subdivisions, I think, contribute significantly to the free-floating sensation conveyed by the piece.