SEVEN: The Magic Number of Harmony

In this blog’s first post, we looked at the physics behind our harmonic/melodic system. But music isn’t just a physical phenomenon. It also involves human listeners. We cannot explain music purely in terms of physics, because we also have to consider the cognitive capacities of human beings. If the physical overtone series helps us to understand why our music uses 12 pitch classes, cognitive psychology helps to explain the key role of another number in music…

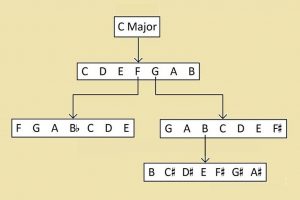

A very famous paper in cognitive psychology posits that the number of items the human mind can grasp at once is the “magical number seven, plus or minus two.” In order to understand systems complex enough to involve more than about seven units, therefore, we resort to “chunking” — that is, we group some units into a whole that is grasped as a single unit. And of couse, some of the component units might themselves be chunks, and so on. In short, we perceive reality in terms of hierarchies.

In a typical tonal music work, the most basic tones are defined by its “scale,” consisting of seven “diatonic” tones, each of which may appear within any octave. Other tones may also be involved — especially in highly chromatic music, such as in late Romantic music and in my own compositions — but they develop out of secondary (or tertiary, and so on) relationships to the seven basic tones. Sometimes those relationships are melodic, such as when a chromatic passing tone is inserted between two of the diatonic tones within a melodic line. Sometimes they are harmonic, such as when secondary harmonic centers are established in the course of a work.

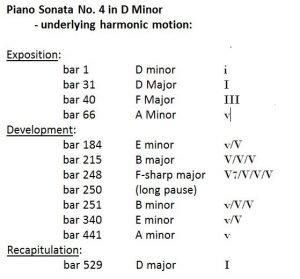

Hierarchical harmonies enable the listener to hear very complex relationships. My fourth piano sonata is in D Minor. Halfway through the development, it cadences on a seemingly very remote F-sharp seventh chord, four levels deep within the harmonic hierarchy (V7/V/V/V). One might think that such complexity would be very taxing for the listener. But in well-written chromatic music, the hierarchical relationships are clear and directly perceptible, so that most of the hard work takes place in the subconscious. The listener can just relax and enjoy music that makes sense to his or her ear.