Proust, Shakespeare, and Sonnet XVIII

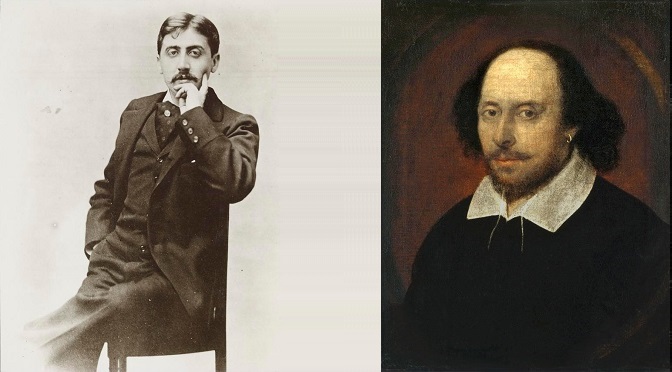

Marcel Proust (1871-1922) wrote just one masterpiece, an epic novel titled À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time). In an advanced French class during my senior year in college, we read the entire seven-volume work. In Proust’s worldview, most of life’s experiences are ephemeral and continually fleeing away from us. But Art — including literature, music, and so on — has the unique capacity of capturing our experiences, rescuing them from the relentless flow of time. Art immortalizes the transient, and that is the central theme of Proust’s great novel.

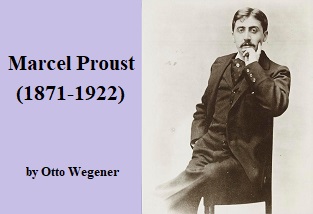

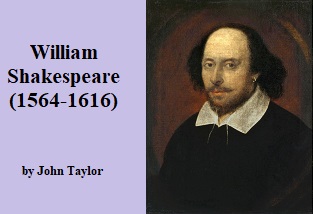

What Proust says in approximately 1.5 million words of florid French prose, William Shakespeare conveyed in the fourteen elegant lines of his well-known Sonnet XVIII. It is unclear to whom this sonnet was addressed, but based on the surrounding sonnets, it is believed to have been a young man, possibly the third Earl of Southampton. The youth’s beauty is likened to a summer’s day, except that his beauty will not fade like the summer season because Shakespeare is immortalizing it in the “eternal lines” of the sonnet itself. The immortalization-through-art message is most explicit in the final couplet: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this [i. e., this sonnet], and this gives life to thee.”

What Proust says in approximately 1.5 million words of florid French prose, William Shakespeare conveyed in the fourteen elegant lines of his well-known Sonnet XVIII. It is unclear to whom this sonnet was addressed, but based on the surrounding sonnets, it is believed to have been a young man, possibly the third Earl of Southampton. The youth’s beauty is likened to a summer’s day, except that his beauty will not fade like the summer season because Shakespeare is immortalizing it in the “eternal lines” of the sonnet itself. The immortalization-through-art message is most explicit in the final couplet: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this [i. e., this sonnet], and this gives life to thee.”

In 1982 I set Sonnet XVIII to music, giving the words to the baritone voice, accompanied by the piano. Wanting to capture the flavor of Shakespeare’s time, I also included an optional part for alto recorder. Although a recording was made in 1985, the singer was not well trained and his vocal range was not quite right for this piece, so I do not share this recording publicly. The work was also performed live with another singer, Donnie Farmer, along with David Swaim on the alto recorder. They presented it in a musical soirée on October 8, 1983 (recounted here), and then in a public recital in December 1984, but neither of these were recorded, so those fine performances faded away from memory like a summer’s day.

Years later I listened to the recording again privately. While the recording was flawed, the melody and harmonies were highly evocative, and I thought the composition captured the meaning and feeling of Shakespeare’s words very effectively. The inclusion of the recorder in particular gave the piece a timeless quality, as if the era of Shakespeare were echoing across time and the bard was reaching to us across the centuries. In Proustian terms, the composition retrieves and eternalizes a lost time.

Naturally, I wanted to revive this work and get it performed with a good baritone — or better yet, to obtain a good recording, thus conferring a certain kind of immortality on the composition itself. In September 2018, I made the acquaintance of a fine, well-trained baritone, Nathan Guc, who was intrigued by the project and who happened to have a predilection for Shakespeare. I also located an excellent young recorder player, Tristän Rush, who was eager to participate and who felt a strong affinity to the music of Shakespeare’s time, which spanned the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods of music history. Both performers were highly enthusiastic about the recording project.

Before making the recording, however, I needed to create a new edition of the score and parts. The composition was written before notation software was widely available, so in late 2018 through early 2019 I converting the old handwritten score into a new modern Finale edition, making some revisions during the process. In the new version, the recorder part was no longer be optional but became an integral part of the music. After much planning and rehearsing over a period of months, we recorded Sonnet XVIII on July 15, 2019.