Nine Preludes: The Pattern Revealed

Composers of preludes frequently present them in a structured key sequence. The preludes and fugues in Book I of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, for instance, are ordered as C major, C minor, C-sharp major, C-sharp minor, and so on, ascending chromatically through all 24 major and minor keys. Bach then repeats the whole sequence in Book II.

In Chopin’s 24 preludes, on the other hand, the procession is clockwise around the circle of fifths, with each major key followed by its relative minor: C major, A minor, G major, E minor, D major, and so on.

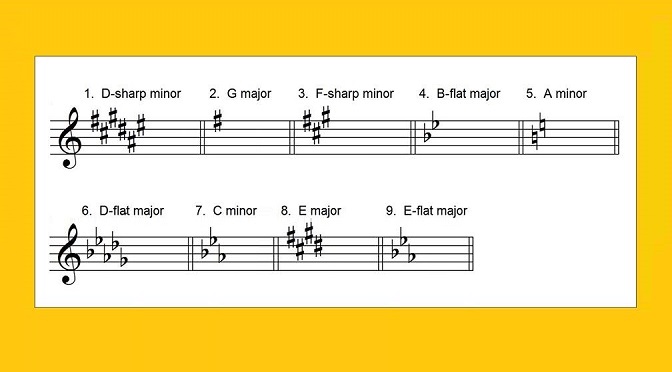

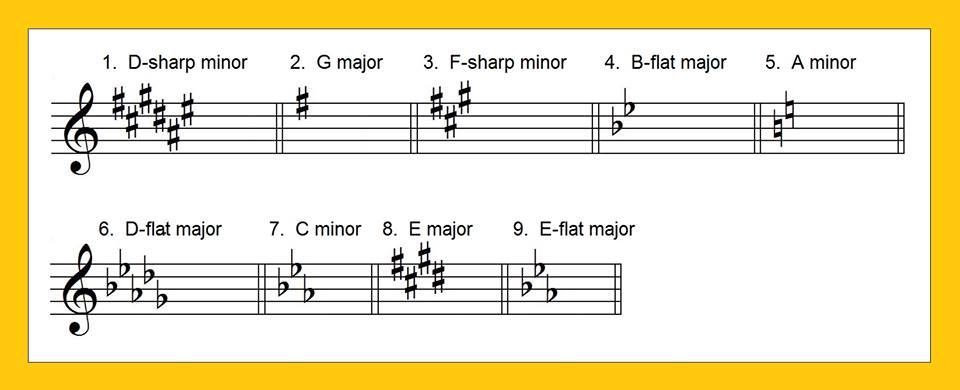

My Nine Preludes for Piano Solo represent some of my best writing for the instrument. Obviously, a collection of nine can only represent a subset of all the possible keys. But the rather strong mathematical side of my personality dictated that the keys should follow a logical pattern (along with certain other symmetries in the set not related to keys). In general, late-Romantic composers like myself prefer to exploit relationships between keys that are not so closely related, and that was one of my objectives in the Nine Preludes. The sequence proceeds from D-sharp minor, up two whole steps, then down a half step, then up two whole steps, and so on. That sequence brings one back to the original key center at the ninth prelude (although spelled as E-flat rather than D-sharp).

As in the key sequences of Bach and Chopin, major and minor keys are alternated (with the exception of the last prelude). The result is that closely related keys never appear side by side, as can be seen by examining the key signatures in the diagram.

I made one exception to the scheme, casting the final prelude in major instead of minor. If I had followed the scheme mechanically, Prelude No. 9 would have been in the same key as Prelude No. 1, an undesirable duplication. More importantly, I wanted to conclude the set with an expression of pure, ecstatic joy — and E-flat major served that spiritual purpose far better than E-flat (or D-sharp) minor.

The whole nine-prelude set can also be viewed as a large-scale motion from minor (D-sharp minor) to the parallel major, another concept that has a rich musical tradition.

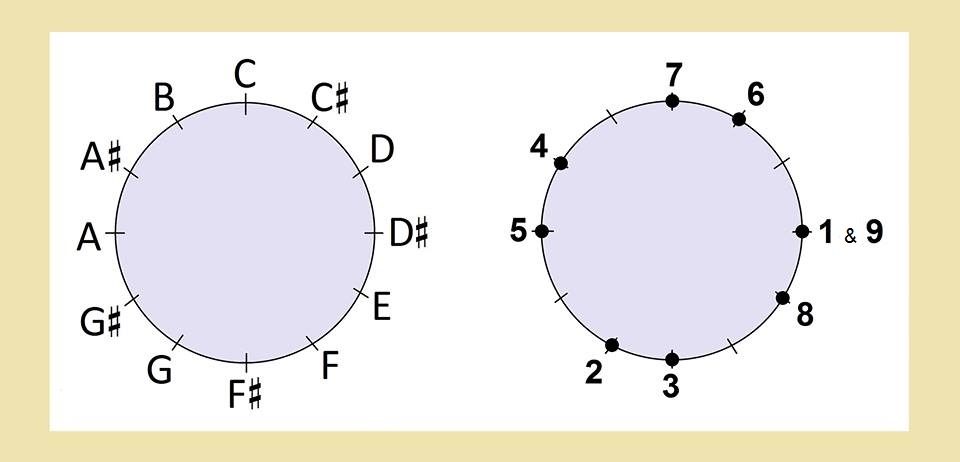

Music theorists often represent musical sets using clock face notation, in which the pitch classes included in a set are represented by nodes on a clock face. The key centers for the Nine Preludes include just eight such nodes, since the first and last preludes (parallel minor and major respectively) map into the same node. When we plot those eight nodes on a clock face, ignoring major/minor differences, the distribution pattern becomes geometrically obvious to the eye.

If you have followed previous posts in this blog, you may recognize this pattern as an octatonic set. The octatonic was first discussed in this post.

A couple of other interesting points emerge from the clock face representation:

• At the midpoint of the sequence, Prelude No. 5 is a tritone away from the first and last preludes.

• The two scherzo-like preludes are No. 3 and No. 7, which are a tritone apart from one another. Prelude No. 3, marked Allegro diabolico has been dubbed the “Halloween” prelude by some listeners. Prelude No. 7 has a similarly playful character, with suggestions of ragtime.

The Nine Preludes can be experienced as a whole, along with the score, in this video: