Melody and Countermelody

We saw in the last blog post how the melody “Puff the Magic Dragon” fits neatly in counterpoint with the theme from Pachelbel’s famous Canon in D. In order to understand better the principles behind effective counterpoint, let us examine a good example of a countermelody from my Prelude No. 2.

The main melody is first presented in the first fifteen measures (the first 1:00 in the recording). It is easy to hear because it is in the upper register, which we can refer to as the “soprano.” Starting in measure 17, the melody is repeated in the soprano, but this time it accompanied by a countermelody in the “tenor” register — i. e., the middle of the keyboard. In fact, in order to play all the surrounding notes, the performer will need to take some of the countermelody’s notes with the left hand and others with the right hand, and I use the bracket-like symbols ┌ and └ to suggest how that can be done. A melody in the tenor range, unlike a soprano melody, is apt to get buried in the texture, so a good performer will give a little emphasis to this countermelody to enable the listener’s ear to hear it just as clearly as the main melody.

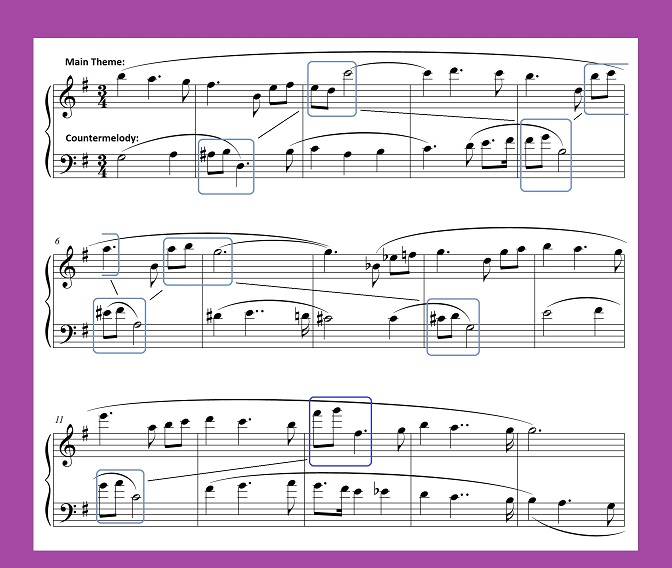

The illustration below strips out everything except the two melodies. A couple of interesting points emerge.

First, the melodies do not in general move in lockstep. Rhythmically, the general pattern is one of interleaving, where one melody surges forward while the other holds a sustained pitch. The ear can therefore focus on each melody in turn, which makes it much easier to track both of them. This interleaving also contributes to the sense that the two melodies are independent, each proceeding on its own. Only in the last few measures of the illustration do the two melodies begin to move simultaneously, but by that point their separate identities are already firmly established.

Second, even though the melodies are independent, they are motivically related. An easily distinguishable motive is heard in the second measure of the Countermelody, consisting of two eighth notes ascending by a step followed by a downward leap. In the next measure, the same motive appears in the Main Theme, except that the idea is inverted, becoming two eighth notes descending by a step followed by an upward leap. After that, the motive is tossed back and forth between the two melodies — a practice known as “imitative counterpoint.” (Within the motive, the size of the leap varies, but it is still instantly recognized as the same motive.)

This motivic commonality enables the two independent melodies to be heard as parts of a cohesive whole — exemplifying a broader aesthetic principle that I think of as “unity within diversity.” The latter principle plays a central role in my compositional process.

As a parting thought: Good music appeals to human beings and is perceived as beautiful because it engages the mind. It is the mind, at least on a subconscious level, that perceives unity within diversity — and we delight in that discovery.