Gradus ad Parnassum

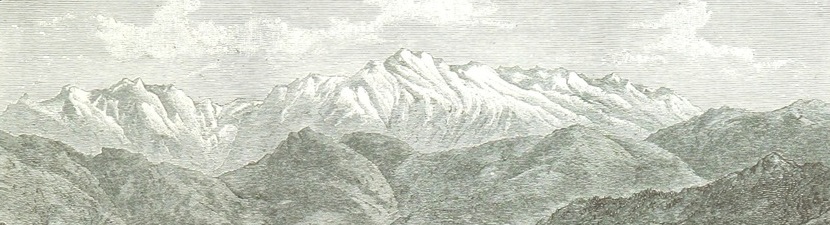

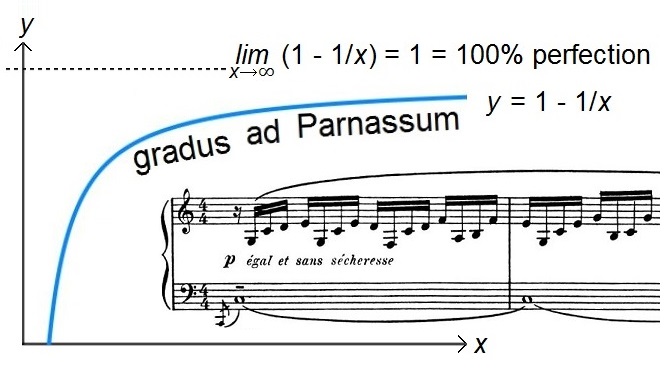

Parnassus was a tall mountain in ancient Greece, believed to be sacred to the gods and regarded as the abode of the Muses. It can be taken as a metaphor for artistic perfection, and historically the expression “gradus ad Parnassum” has been used to describe a series of steps toward such perfection, especially in music. The great contrapuntalist Johann Joseph Fux (who influenced Heinrich Schenker, the theorist who developed Schenkerian analysis) published a textbook titled Gradus ad Parnassum, which is believed to have been studied by the young Mozart and was highly regarded by both Haydn and Beethoven. Several other authors used the title for sets of technical or pedagogical studies for the piano and other instruments. Debussy paid satirical homage to such studies in his “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum” (from the suite Children’s Corner), which many of us learned as youngsters as one small step in our journey toward pianistic perfection.

The drive toward perfection seems to be inherent in the artistic impulse, yet it is nowadays regarded with suspicion in some quarters. Since human beings are incapable of true perfection, the fear is that a perfectionist ideal can only lead to frustration and paralysis.

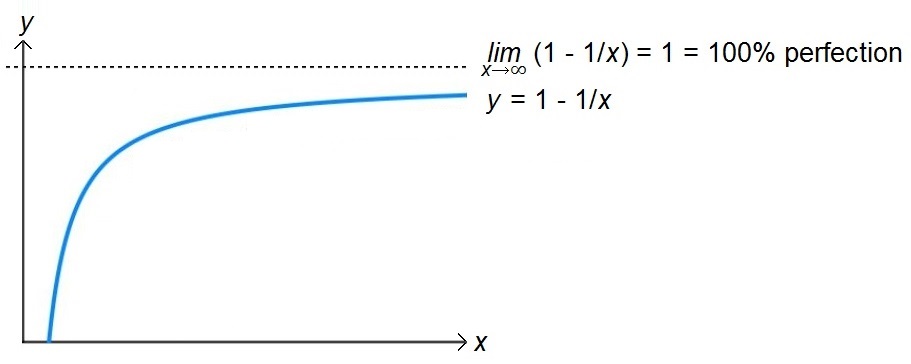

I look at it differently. I conceive of perfection as analogous to a mathematical limit. A limit may never actually be reached by a function, yet given sufficient time, it may be approached arbitrarily closely. Most importantly, the limit helps us to comprehend the shape and direction of the function.

We pianists may hold an ideal in our minds for how a beautiful piece should sound, with the tones in every phrase and chord perfectly balanced, every detail of the flow through time precisely determined, every phrase or section shaped with a view to the aesthetic effect of the whole. The ideal then guides our practice, and as we work on the piece day by day, we continue to move toward that ideal. Without that conceptual ideal, our practice would be unfocused, directionless, and unlikely to produce the beauty we seek.

In reality, however, our progress is even more complex than that, for even as our physical realization evolves toward our mental ideal, that mental ideal must itself be constantly evolving, progressing through its own series of stages, evolving toward artistic Parnassus. As our vision gradually pierces through the mists that surround that peak where the Muses dwell, we perceive it with increasing clarity.

Since we are mortals and not gods, our efforts must be finite. Therefore, at some point we must decide that our realization of the piece, although still not quite perfect, is nevertheless worthy of performing before a particular audience or committing to a recording. After that, we may decide to rest for a while, turning to other repertoire in order to deepen our understanding of our art — only to return to the same piece years later in a lifelong quest to take it to a new level.

The perfect should never be the enemy of the good. Since we are not gods, we must accept the fact that we can never inhabit Mount Parnassus. It will always remain tantalizingly beyond reach. Yet while our steps can never take us literally to the top of Parnassus, we can nevertheless take step after step toward it, approaching it in the limit. The knowledge of our imperfection should not deter us in the slightest as we continue our progress toward that lofty peak.

Well said. I wrestle often with the fact that I am merely an “okay” composer. However, it is perfectly fine to just be okay. Still, it is tough to love “classical” music, as time has subtracted all the “okay” composers from memory and only masters and their masterworks remain. I feel that often makes “okay” feel “terrible”. Your blog was a welcome reminder that music with good and bad moments, flaws and brilliance sharing space deserve to be heard too. Sometimes we connect more with an “okay” rendering than a “flawless” one.