Curiosity of the Composer

In a previous blog post, I shared some advice I have offered in response to queries from young composers. As I commented in that post, a thorough knowledge of music theory — including harmony, counterpoint, and musical form — is essential for successful composing in a tonal style. But even before ever receiving any formal training in these subjects, a composer should have a natural curiosity about what makes music work, and about why certain passages, harmonies, and even individual notes have a particularly vivid effect on our perception. This curiosity makes us wonder at the effects of music even as young children, long before we have the intellectual apparatus to explain them, and it is part of the background experience that we bring to the act of composing many years later. Good composers, I believe, tend to have an intuitive awareness of these matters even before they learn music theory, in the same way that good novelists are naturally attuned to human behavior and motivation even if they have never formally studied psychology.

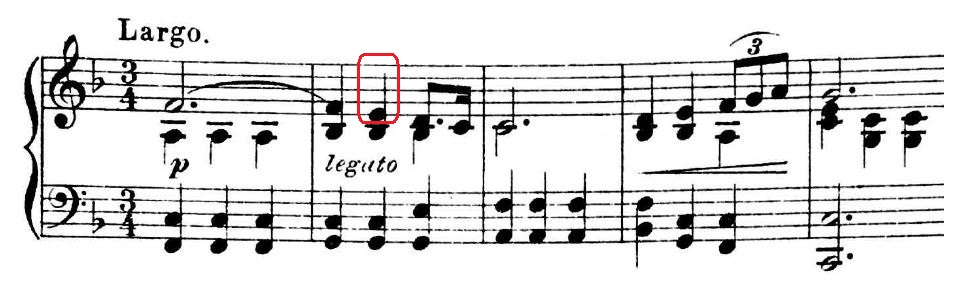

Like many young piano students, I learned the six sonatinas of Muzio Clementi, Op. 36, when I was about 11. They were among the first real classical pieces I could play in their original form, a heady experience for an ambitious young student. The first two of these sonatinas were pleasant enough, but what really struck my imagination was Sonatina No. 3, which seemed to venture into a new world of beautiful, expressive sound. Consider, just as a single detail, that wonderfully expressive B in the melody at the beginning of the third measure of the first movement.

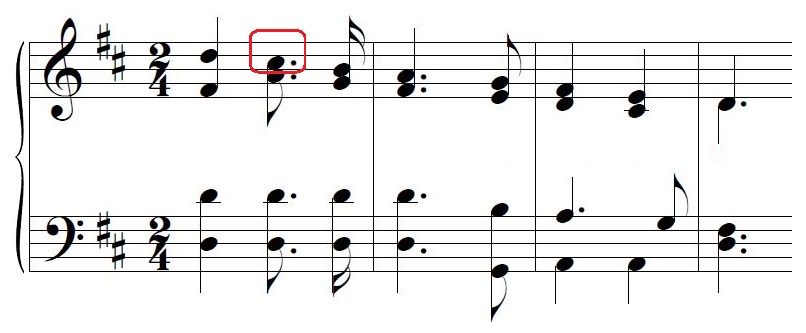

At that age my knowledge of theory was limited; I think I understood keys and key signatures well, but did not yet know the full nomenclature of intervals. Therefore I could not explain what was happening in words. Today, with the vocabulary of an adult musician, I can point to the delicious tritone dissonance between the melody note B and the accompanying F. Normally, the seventh scale degree functions as a leading tone, resolving upward. But sometimes, as here, it serves as a nonharmonic (passing) tone and resolves downward, and this departure from its normal function seems to add an extra piquancy to the note, especially when it appears in a metrically strong position, as in this case. This descending seventh degree also plays an expressive role in other familiar melodies, both in classical melody and popular song, melodies that also captivated my young musical imagination. Note the lovely and dramatic descending seventh degree in the well-known Largo from Handel’s Xerxes (which I played in a string quartet a couple of years after learning the Clementi):

The music for the famous “Joy to the World,” which again uses the dramatically expressive descending seventh degree, was composed by Lowell Mason, who may have been influenced by Handel’s Messiah. In this case the seventh degree is a nonharmonic tone against tonic harmony, so instead of a tritone, it creates a major-seventh dissonance, which becomes all the more dramatic since it arrives on the beat and then resolves at a comparatively weak metrical point.

In the Clementi movement discussed earlier, the expressive use of the tritone (here B/F) is not limited to the opening of the movement. There is a passage in the recapitulation (actually an extended version of a similar passage in the exposition), in which an entire chain of tritones appears. Most of them occur within vii˚ harmonies, with dominant or secondary-dominant function, although one of them is part of an Italian augmented-sixth chord.

Although I knew little of harmonic analysis at that age, I remember finding the harmonies in this passage to be especially thrilling. The chromaticisms seem even more adventurous and colorful in the context of Clementi’s overall diatonic writing. I do not intend to imply that Clementi’s music is necessarily exceptional; if I had instead been exposed to works of some of his contemporaries, I would no doubt have noticed similar devices and experienced similar moments of exhilaration.

A young composer, I believe, develops a vivid awareness of such sensory experiences, becoming sensitive to the perceptual effects of particular melodic shapes, harmonies, and rhythms long before he or she acquires the tools of music theory to analyze them intellectually.