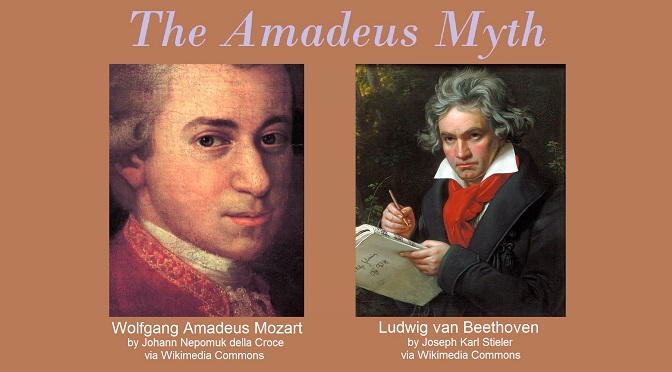

The Amadeus Myth

The popular film Amadeus, based on a stage play of the same name, depicts Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart from the vantage point of his rival Antonio Salieri. Mozart’s music is depicted as a miraculous gift, coming to the composer in completed form, unbidden and effortlessly, in contrast to Salieri’s own mediocre works, produced by countless hours of painstaking toil. In Salieri’s view, God speaks directly through Mozart and the latter is but the passive recipient, the amanuensis of a divine creation.

The movie depicts a common perception, inherited from the nineteenth century and refuted by modern musicology, which contrasts the supposedly effortless compositional method of Mozart with that of Beethoven. We know from Beethoven’s sketchbooks that his initial sketches typically contained only pale suggestions of his final product. Only after countless edits and revisions does Beethoven’s great genius finally emerge.

Other composers, both famed and obscure, seem mostly to follow the more evolutionary model of Beethoven. Even after Chopin’s works were published, he continued to revise them in copies used by his students, thus producing headaches for editors who seek to publish definitive editions. Liszt made numerous revisions to his own works. Rachmaninoff made major revisions in 1931 to his Second Piano Sonata (originally published in 1914), making the texture sparser and the work more economical. On a less lofty level, over the last couple of years I have made significant revisions to three of my own compositions, originally written in 1983, 1986, and 1991, curtailing excesses I no longer found satisfactory or rewriting passages in accordance with my current more mature perspective.

It is now known that Mozart was not really exceptional in this regard, that his compositional process (like that of Beethoven and others) involved sketches and early drafts, although many of those were destroyed by his widow after his death. Much of the mythology about Mozart seems to have been propagated in the early nineteenth century by the publisher Friedrich Rochlitz, who among other things offered a purported letter in which Mozart supposedly claimed that his musical ideas came to him without effort: “Whence and how they come I know not, nor can I force them.” Scholars now recognize Rochlitz’s letter as a forgery. In one of his real letters to his father, Mozart wrote: “You know that I immerse myself in music, so to speak — that I think about it all day long — that I like experimenting — studying — reflecting.” The composer’s words reflect a theme I have frequently voiced in my own writings: Music is a cognitive process, not a matter of sudden mystical inspiration.

In music, as in other fields, Thomas Edison’s observation applies: “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.”