Sketches

In my file cabinet there is a thick folder labeled simply “Sketches.” It contains musical sketches, ranging from early compositional attempts to incipient musical works, collected over the last half century. (I remember making such sketches even earlier, in my high school and even grade school years, but these oldest sketches are lost.) Most of these are on loose-leaf manuscript paper, although some are in a ringed notebook and others are on scraps of paper, even backs of envelopes. These latter were bits of inspiration hastily recorded when they came to me, often in the middle of the night or when I was away from home and had no manuscript paper available.

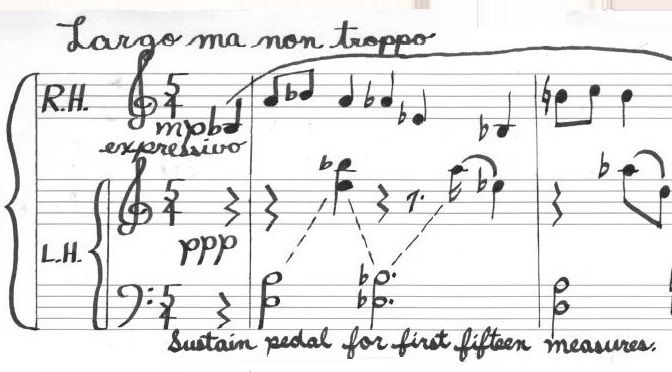

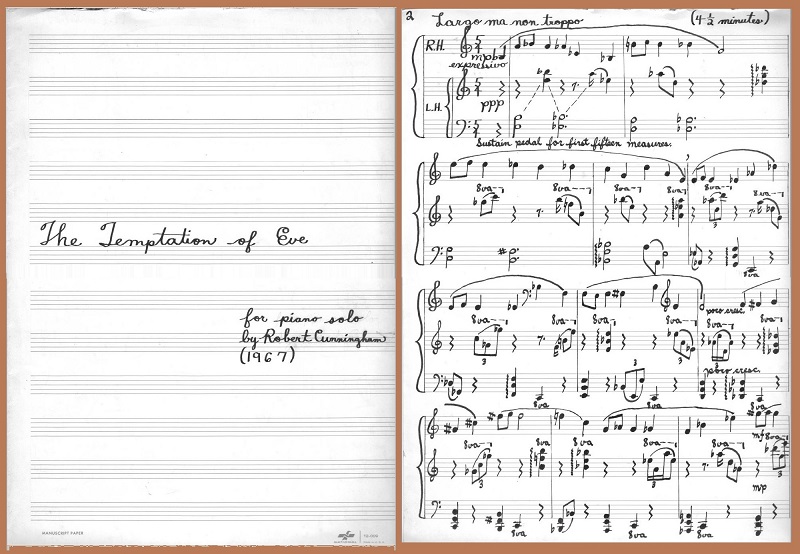

A few of these sketches contain material that eventually found its way into my final compositions, such as the main theme of my Rhapsody for Woodwinds and Piano. But most are attempts at composition that clearly reflect my personal style but which I abandoned, presumably because they did not meet my standards. Some were written for classes in my youth. There is a first movement for a string quartet, written for a Juilliard class. There are several little pieces I wrote for an unofficial after-hours composing class when I was an undergraduate, all in the non-tonal style that was expected of us. The pic shows the beginning of one of those pieces, set for piano solo and whimsically titled “The Temptation of Eve.”

As can be seen, the piece explores the possibilities of melodic motion through successive perfect fourths, as well as motion by half steps and their equivalents (i. e., major sevenths and minor ninths). Because tonality was strongly frowned upon in that class, I was not able to develop my personal style there, but I was becoming familiar with some of the basic mechanics and techniques of composing. Not until about fifteen years later, after a great deal of other efforts and experimentation, would I come to regard myself as a real composer.

In his book The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle explores how expert talent develops. High-level talent is not inborn, but must be developed from modest beginnings over many years of practice. A compelling example was the Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë — who dazzled their Victorian peers with such great novels as Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. To observers at the time, their literary talent appeared almost supernatural, seemingly coming from nowhere. Only in recent years have biographers uncovered the series of early, immature attempts from their childhood that preceded the great works for which the Brontës became famous. As Coyle says frankly of these predecessors: “Their writing, while complicated and fantastical, wasn’t very good.” Nevertheless, these sketches laid the necessary foundation for later greatness.

In his book The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle explores how expert talent develops. High-level talent is not inborn, but must be developed from modest beginnings over many years of practice. A compelling example was the Brontë sisters — Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë — who dazzled their Victorian peers with such great novels as Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. To observers at the time, their literary talent appeared almost supernatural, seemingly coming from nowhere. Only in recent years have biographers uncovered the series of early, immature attempts from their childhood that preceded the great works for which the Brontës became famous. As Coyle says frankly of these predecessors: “Their writing, while complicated and fantastical, wasn’t very good.” Nevertheless, these sketches laid the necessary foundation for later greatness.

Most of the sketches in my folder fit in the “not yet ready for prime time” category. Works like “The Temptation of Eve” are the original sins that one prefers to hide forever from public view (which is why you see only the first page here). Other sketches contained the seeds for worthwhile works, but those seeds would have to be planted and carefully nourished before they could develop into publishable compositions.