Recording Dynamics

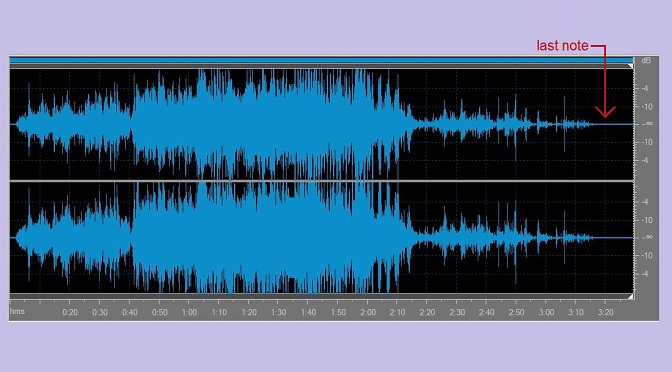

Producing recordings of classical music, especially Romantic music, presents unique challenges. Consider the audio profile of my Prelude No. 5 (both left and right channels are shown here):

The piece has an “arch” shape that is not unusual in Romantic pieces, starting quietly, rising to a loud climax, then ending very quietly. In this case the last note is so quiet that it does not register on the graph, even after the scale has been blown up enough to truncate many of the peaks in the music.

When music with such a wide dynamic range is presented to the general public on the web, we want to ensure that everyone will be able to hear that last note, even those who do not have high-quality speakers or headphones. But we also do not want to amplify the music to the point where a significant portion of the louder passages are distorted. So we aim for a compromise, and not always a very satisfactory one.

Popular-music recordings do not have this issue so much, because the music tends to have a much narrower dynamic range. My theory is that a lot of popular music is intended as background, as something to listen to while you are driving or getting in your treadmill workout. You don’t want background music to be so quiet you can’t hear it over the treadmill noise, or so loud that it distracts you from what you’re doing — namely, something other than listening to music.

In the nineteenth century, people listened to Chopin’s music in the quiet salons of Paris, and he became known for his delicate pianissimi. If the Polish master were starting out today, no one could detect his pianissimi on their car radios over the road noise.

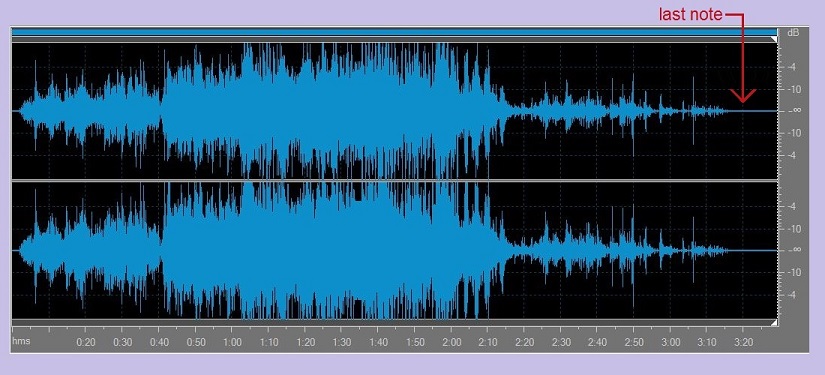

Wrestling with this problem in Prelude No. 5, I finally decided to amplify the original recording by 6dB, which seemed just enough to make the last note easily audible without headphones. But I wondered how others dealt with it. I decided to check the sound level in a video by YouTube recording star Valentina Lisitsa. I chose her performance of Chopin’s Etude No. 3 because its arch shape was similar to my prelude.

Of course, whenever you listen to Lisitsa play, you are instantly captivated by her marvelously luscious sound and forget what you were doing. But once I managed to break out of the Valentina trance, it seemed (based on my ear, not device measurements) that she and her producers had arrived at a decision similar to mine. The sound level was just sufficient to ensure that Chopin’s final note would be audible without my headphones.

If you have a pair of good headphones, I would definitely recommend them when listening to my Prelude No. 5 and other recordings. But whatever device you are using, feel free to adjust its sound level to your own preference. Sound levels, after all, are relative to the listener. If you were sitting in the back of a Parisian salon in the 1840s and you could not hear Chopin’s pianissimo, you would have adjusted your personal sound level by moving closer to the front of the room.