Heinrich Schenker’s Musical Grammar

To say that music is a language is not just a metaphor. Music has syntactical structures very akin to those of spoken language, and we now know that the processing of music strongly involves the parts of the brain associated with language. The relationship between music and spoken language should not surprise us when we consider that words and music were originally united in the form of song. Music theorists have been aware for centuries of the kinship between music and other languages. In the early twentieth century, Austrian theorist Heinrich Schenker (1868-1935) introduced a graphical system for conveying the grammar and syntax of a piece of music, which is now in widespread use among theorists and is known as Schenkerian analysis.

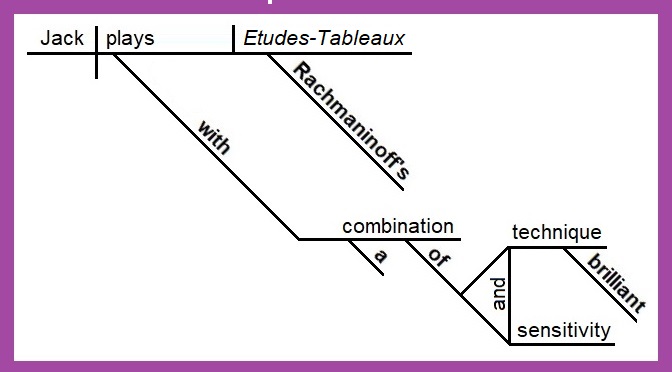

Some of us are old enough to remember sentence diagramming, a graphical technique formerly taught in grammar classes. A sentence diagram can show clearly how a simple Ur-sentence, like “Jack plays”…

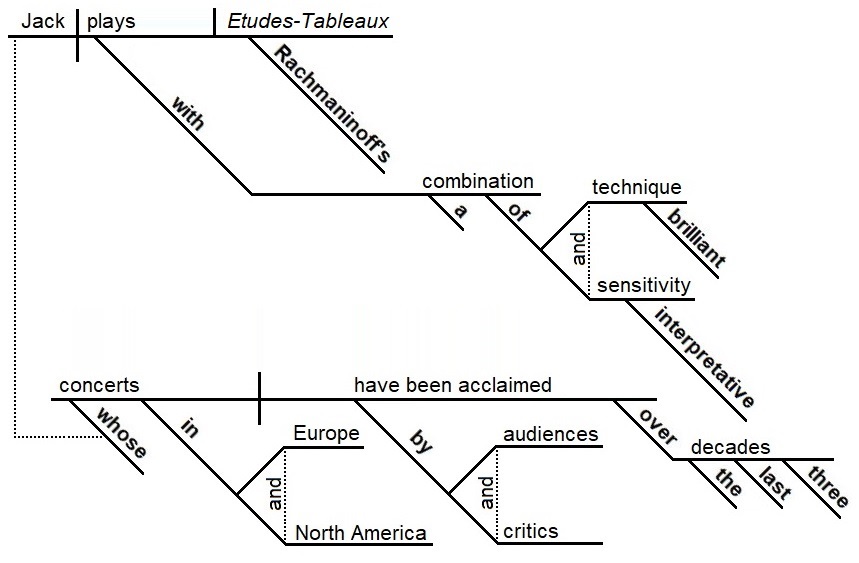

…develops, through successive modifiers, modifiers to modifiers, and so on, into a much more elaborate sentence with a precise syntactical structure: “Jack, whose concerts in Europe and North America have been acclaimed by audiences and critics over the last three decades, plays Rachmaninoff’s Etudes-Tableaux with a combination of brilliant technique and interpretative sensitivity.”

Schenkerian analysis elicits the structure of a tonal composition in much the same way — although instead of “modifiers,” Schenkerians use terms like “ornamentation” and “embellishment” and “prolongation.” At the core of any well-constructed piece of tonal music, according to Schenker, is a fundamental structure, or Ursatz, which typically might consist of a melodic descent in the treble from the third scale degree to the tonic over a I-V-I arpeggiation in the bass. The Ursatz forms the background, from which the work develops, through successive layers of embellishment, into multiple layers of middleground and foreground.

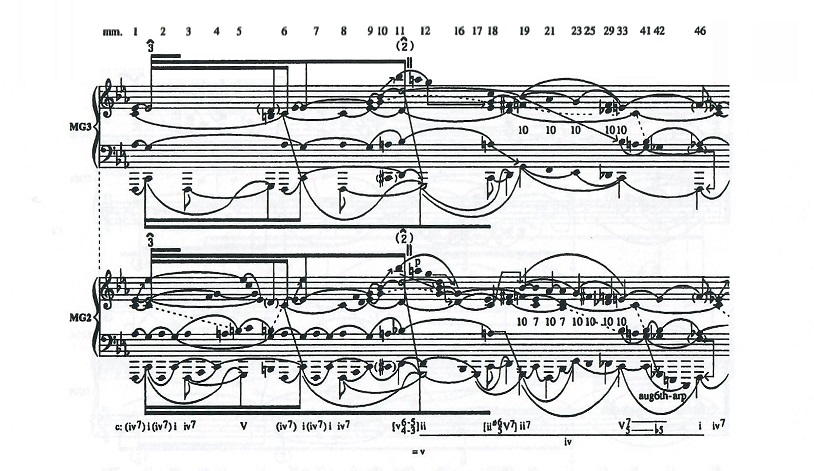

The unembellished Ursatz, however, is relatively dull, and at that level the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony might not differ from “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” The real genius of a great work, therefore, appears in the middleground layers, which are displayed through elaborate graphs in Schenkerian analysis.

Schenkerian analysis, by the way, goes much further than the Roman-numeral analysis traditionally taught in theory classes. Roman-numeral analysis is useful for understanding how harmonies (triads, seventh chords, etc.) are built vertically from roots, but many harmonies in advanced music arise from horizonal (melodic) movement within voices within the contrapuntal structure. The latter can be seen clearly in a Schenkerian graph.

Schenker’s technique is especially useful for analyzing the structure of the chromatic works of late Romanticism, where (not surprisingly) we see some special prolongational techniques not present in earlier composers, some of which go beyond Schenker’s original analyses. I used Schenkerian analysis extensively in my 1999 PhD dissertation to analyze works of Rachmaninoff. The sample graph below is taken from that dissertation and shows two middleground levels from Rachmaninoff’s Etude-Tableau, op. 39/1. Indeed, our friend “Jack” from the sentence diagram above may have performed this work on one of his European tours. 🙂

Just as a sentence diagram combines English text with a few simple graphics, you will notice that a Schenker graph combines musical notation with a few special symbols.

Which books (or other study materials) on Schenkerian analysis would you recommend to a young composer?

First, I should caution that I don’t use Schenkerian analysis for purposes of composing myself, just as I wouldn’t use a book on English grammar to help me write a novel. Nevertheless, it’s a great tool to help one to understand what’s going on in a piece of tonal music. Here’s a great starting point: https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Schenkerian-Analysis-Allen-Forte/dp/0393951928

As a former music theory student who now teaches 6th-grade language arts, I’ve long noticed the similarities between sentence diagramming and Schenkerian analysis. Your post is a welcome confirmation.

Thanks, Suzanne, and thanks also for reading!