Compositional Process: The Melody of Life (Part 1)

My composing involves a blend of musical intuition and analytical judgment. Melody is central to my music, and typically I begin a new composition by defining its principal melody. In May 2017 I was commissioned to write a piano piece to honor two ladies who were struggling against cancer. (The story behind this work is recounted in detail in a two-part series beginning here.) That piece would become my Nocturne No. 2 for Piano, and I wanted it to capture the infinite beauty of life, in the hope that this music might help to inspire in its two honorees the passionate commitment to life that their battle required. So the piece began with my feeling about life, a feeling of solemn awe and wonder. After a couple of days I began to translate that emotion into a melody, beginning with a phrase or two in my head, which I then sat down at the keyboard to develop into a whole. I thought of it as the melody of life, and in fact I would later subtitle the completed work “Passionate Melody of Life.”

So I was not thinking consciously about music theory as I composed the melody, but was mostly guided by my subconscious. Of course, my subconscious was influenced by almost sixty years of music studies, including intensive training in theory. But on a conscious level, I was no longer thinking about theoretical rules, but instead searching for the melody notes and harmonies that would express the intended feeling.

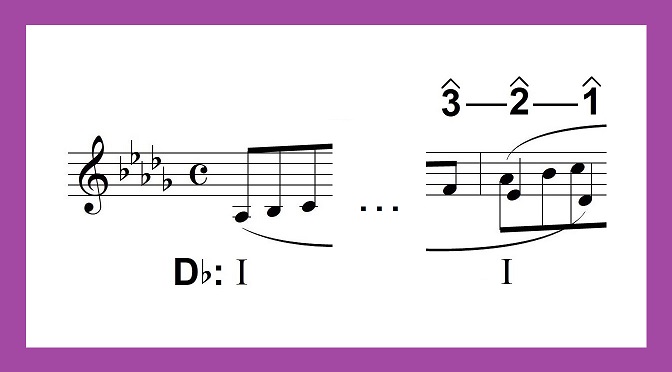

In retrospect, however, the structure of the melody that came out of that process can be readily described in theoretical terms. The melody of life first appears in measures 3-11, shown here along with the principal harmonies. A second iteration of it can be seen starting an octave higher in m. 11 at the end of the excerpt.

The melody is binary (two-part) in form; in the final score, the division between the two parts is emphasized by a poco ritardando in the second half of m. 6, followed by a return to tempo in the next bar. The skeletal outline of the first part, in Schenkerian terms, is an interrupted descent from scale degree 3 to 2, accompanied by a harmonic motion from tonic to dominant. In the second part, scale degree 3 reappears initially in m. 9 over vi harmony, which can be regarded as a tonic substitute. The melody then descends (in mm. 10-11) from 3 through 2 to 1 along with a harmonic motion through the dominant and back to tonic. The very strong harmonic progression in the last few bars creates a feeling of inexorable forward impetus toward the melody’s conclusion.

Although I have included some Schenkerian symbols here to help illuminate the structure, I should emphasize that I do not use Schenkerian analysis as a compositional method. It is simply a convenient way of understanding what I have composed after the fact.

An unusual wrinkle in this structure is that scale degree 2 of the last descent is temporally displaced relative to the bass. Instead of appearing over the dominant in the latter part of m. 10 as one might expect, it is delayed to the downbeat of m. 11, over tonic harmony. That temporal displacement makes possible an aesthetically pleasing overlap between the finish of the first iteration of the melody and the start of the second iteration. As a consequence, the second iteration of the melody of life seems to grow out of its predecessor — much as life itself arises from previous life.

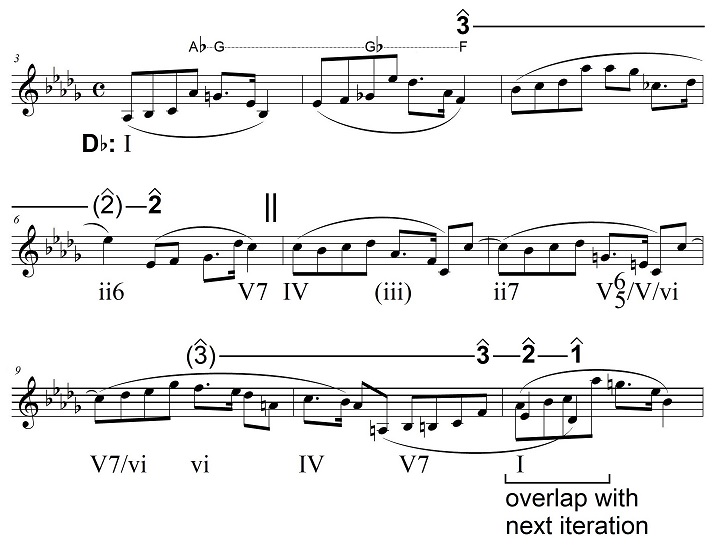

This overlap pattern repeats through most of the piece, even as the iterations become increasingly elaborate. Only in the last major cadence, in mm. 53-54, is scale degree 2 of the descent directly supported by the dominant:

This last major cadence therefore conveys a true sense of finality, and if a Schenkerian graph were made of the piece as a whole, the descent of the Urlinie would undoubtedly be placed at that spot.

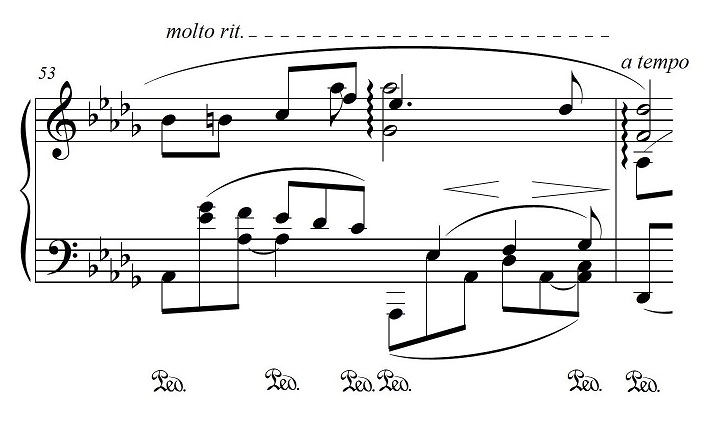

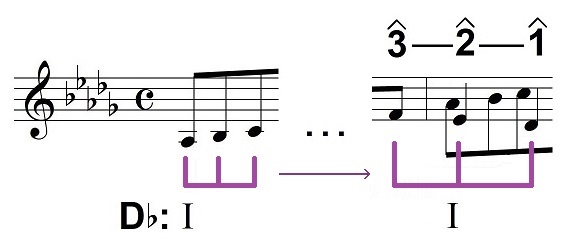

Looking again at the entire melody, I made a most remarkable observation: Its last three notes, which descend by whole steps to scale degree 1 (F-E♭-D♭), mirror its first three notes, which ascend by whole steps from scale degree 5 (A♭-B♭-C):

I think this dualistic symmetry is an important contributor to the organic unity of the melody. It arose by subconscious intuition, and I became consciously aware of it only after the melody was complete, at least in rough form. But once I noticed it, that epiphany led me to start analyzing other three-note linear patterns within the melody — and those patterns turned out to be the key to developing the rest of the piece, as I will explain in Part 2 of this series.