Dualism in a Rachmaninoff Prelude

Harmonically, music of the classical period was based on tonic-dominant polarity. The subdominant served only a subsidiary role, introducing the dominant or else embellishing either the tonic or the dominant.

The chromatic music of late Romanticism, however, tends more toward a dualistic model, where dominant and subdominant are equal and opposite forces, flanking the central tonic. This dominant/subdominant opposition, as it turns out, is closely related to the major/minor opposition, with dominant naturally aligned with major and subdominant with minor. One consequence is that the minor form of the dominant, where the leading tone is absent, has a significantly weakened dominant function.

In late nineteenth-century harmonic theory, dualistic thinking was prominent in the writings of theorist Hugo Riemann (1849-1919). As I point out in my 1999 PhD dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s harmony, there is reason to believe that Rachmaninoff would have become well acquainted with Riemann’s dualistic thinking around 1902-1904, if not earlier.

In any case, the subdominant plays a strong and independent role in several of Rachmaninoff’s works, including his Prelude in B Minor (op. 32/10), which I recorded in 2018. The prelude climaxes in a highly embellished subdominant ninth (e9) chord in measures 45-48, ushering in an elaborate cadenza that further emphasizes the subdominant harmony. In my recording, I hold the pedal past the end of the cadenza, right up to the return of the tonic at the start of bar 49, thus preserving the whole rich subdominant sonority — and especially the fundamentals E1 and E2 — in the bass.

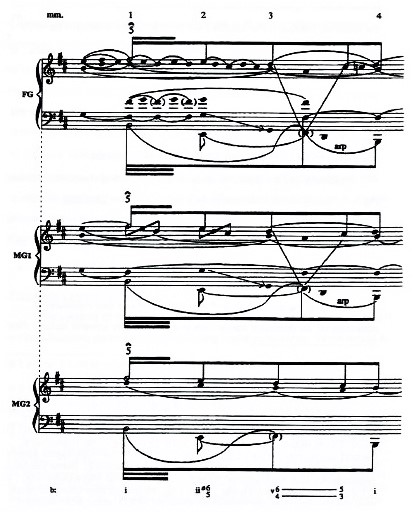

Some commentators have suggested that the opening bars are tonally ambiguous and that the tonal center could potentially be either E or B. This Schenkerian graph comes from my dissertation and depicts the foreground and middleground for the first four measures:

As can be seen, the phrase’s basic harmonic structure is a conventional tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic sequence. Consequently, I do not regard the tonality as ambiguous. Nevertheless, the subdominant does play an outsized role here. At the same time, several factors attenuate the dominant component of the progression. Most obviously, the leading tone (A♯) is absent, replaced by the natural-minor seventh degree (A). In fact, pitch class A♯ is conspicuously absent from most of this prelude. It briefly appears in measure 17, but there it functions not as a leading tone but rather as an embellishment to the subdominant. After that, it reappears only in the final cadence (mm. 57-58), and even there the strength of the dominant is lessened by other factors.

Notice also that melody tone C♯5 near the end of measure 3 in the graph is harmonized locally by a mediant root (D2) as part of a tonic arpeggiation in the bass, producing a hybrid local harmony that mixes dominant and tonic functions — thus further de-emphasizing the dominant.